I’m a parent and a person who watches schools for a living. This guarantees I’m a fussy school-shopper. In kindergarten, we tried three schools in five months before settling down at dual-language Namaste Charter School. I thought Antonia had found a home to last.

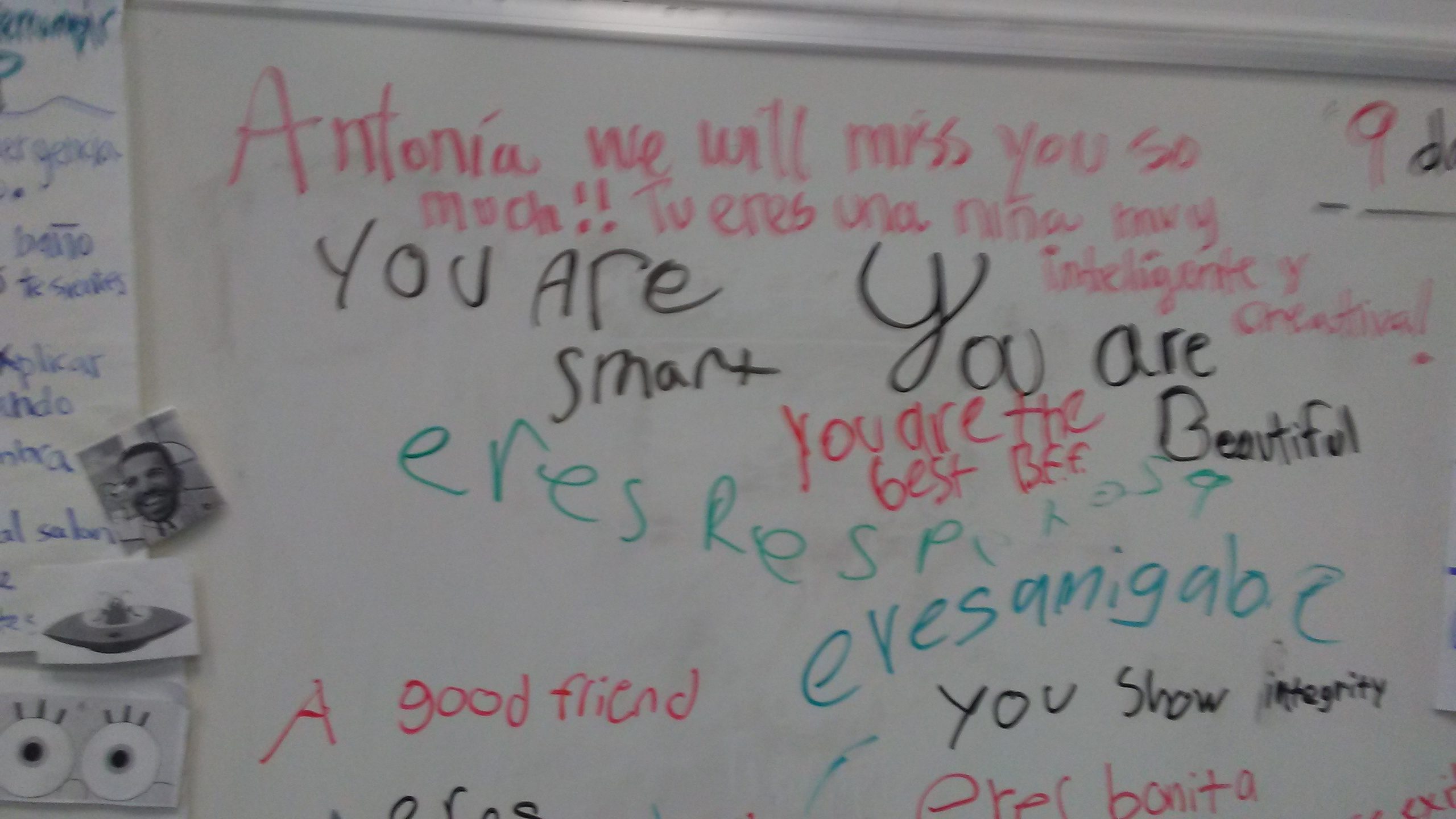

Unfortunately, I was wrong. After starting the year at Namaste, with Halloween and Dia de los Muertos in the air, Antonia said goodbye. The Monday after her despedida (farewell party), she walked through the doors of Chavez Multicultural Academic Center, our neighborhood school in Back of the Yards.

If you were to look at demographic data, you might think I was crazy. Why would I leave one mostly free-lunch, predominantly Latino school for another school that is less affluent and even more segregated? And why would I leave after the school year had started, a kind of switch that can throw off even the best-supported child?

To understand my decision, you’d have to know both the data and the inside of the two buildings. If you look at NWEA test scores—standardized tests that Chicago schools use to measure both growth and achievement—you’ll see Chavez outperforms Namaste by a lot.

In fact, it is one of the dozen highest-achieving schools in the city for math. It’s not a gifted center. It’s not in a wealthy neighborhood. It just has what all schools need: an excellent principal who knows how to marshal resources and build a strong and happy faculty, coupled with dedicated teachers who know their job and love it.

A third data set confirms that more than just drill-and-kill is driving those high test scores at Chavez—the annual climate surveys given to parents, teachers and older students. Taken together, it’s clear Chavez has something very good going on for kids.

I’ve known that for years. I manage a blog about education, and I’ve written about Chavez before. So, why didn’t I put my own daughter there in the first place?

For our family, dual-language instruction was our highest priority. Antonia’s father is from Mexico City and arrived here as an adult. Her tias and most of her primos and primas are all in Mexico. But her Papá’s job means they see each other mostly on the weekends, and my Spanish isn’t good enough to help Antonia reach her full potential to be bilingual and biliterate. For us, Spanish isn’t a nice-to-have; it’s a must.

At first, Namaste not only helped us achieve our language goals, it did much more. Back in kindergarten, her teacher set up a classroom where children explored engineering, black history, countries from all over the world (she got Nicaragua and we learned to make gallo pinto, a style of rice and beans) and famous women like Jane Addams. She ate healthy, tasty lunches and took dance and yoga in gym class.

Unfortunately, Namaste has traveled a rocky road since those happy kindergarten days. At that time, Namaste’s founder, Allison Slade, was transitioning out of running the school she had led for 11 years.

I thought a strong succession plan was in place. The new leader was spending a year as co-director, after which he would take the reins. We had instructional leaders for the K-4 grades and the middle school (5-8). I thought the transfer of power would be smooth.

It didn’t work out that way. The successor left within 18 months. As so often happens with both district-run and charter schools, Namaste went through tough times trying to find the next leader. Teachers began to leave. The school lost focus, especially in its signature area of health and wellness.

As someone who has seen many schools ride these rapids, I watched the drama with a certain level of detachment.

Then I put my mom hat on and asked myself, “How is Antonia’s school experience? Am I happy with it?”

For most of our time at Namaste, I could say yes. I was happy to see her learning in Spanish and joining a small, tight-knit community. During third grade, her father and I separated. Our school invests in a full-time social worker, who was a huge help to Antonia as she made the adjustment.

But over time I noticed other things falling by the wayside. After-school offerings thinned out. Gym became more traditional, a weak fit for Antonia. Math instruction seemed to be an afterthought.

Mostly, I didn’t talk about these frustrations. Instead, like so many parents, I put my shoulder to the wheel. I chaperoned and brought in snacks. I went to the fundraisers. Because I have insider knowledge around schools and Chicago Public Schools, I helped write grants. For two years, I served on Namaste’s Bilingual Advisory Committee.

But over the last few months, it became evident we needed to make a change. In kindergarten, Antonia was scoring in the middle 90th percentile on the selective-enrollment test. At conferences last June, her NWEA scores came in in the high 60th percentiles. OK, it’s not an apples-to-apples comparison, but it tells you something that’s not good news. Moreover, it’s not her ability that has changed; it’s the effect of weak instruction.

In September, I attended a meeting of Namaste’s board, where our current school leader, Natalie Neris, whom I like and I think will stick, laid out a three-year strategic plan for the school. But by the time that plan is fully executed, Antonia will be a seventh-grader. We can’t wait that long.

We are very lucky to have a great neighborhood option. I went home and told Antonia, “You let me know when you are ready, and we will go to Chavez.” A few weeks later she said, “Mom, I’m ready.” In a week she was in her new school.

It has been agonizing to come to this point. Both Antonia and I made good friends at Namaste. I worry that she could be losing all those friends she has known since kindergarten. Losing connection with the school social worker hits both of us hard. As a charter, Namaste is somewhat insulated from the whims of the central office. I will miss all these things dearly.

And yet, it’s time to go. Antonia’s new math and science teacher is a woman I have known since she was a high school student at Jones College Prep. She’s now leading professional development in math instruction for her colleagues. She grew up in the neighborhood and loves the people here. Her mom has been a community representative on the Chavez Local School Council for as long as I’ve lived here. She’s not going anywhere.

That’s the kind of experience I want my daughter to have—being taught by someone who not only shares her language and cultural background but also has the particular experience of growing up in Back of the Yards.

On her first day at Chavez, Antonia told me, “I learned long division today and I love it.” She made three new friends right away, too. At bedtime she said, “I’m looking forward to going to school tomorrow and learning. I haven’t felt that way in a long time.”

I don’t want to have to choose between a dual-language program and strong math instruction. But if I have to make that choice, I will choose math. I know both these schools inside and out. I know where my daughter will get what she needs right now. And I’ll probably get to work pushing Chavez to go dual-language. Cause, yep, I’m that kind of mom.

Maureen Kelleher

Latest posts by Maureen Kelleher (see all)

- CPS Parents Wanted for Research Study - March 27, 2023

- Tomorrow: Cure Violence with #Belonging - August 17, 2022

- Still Looking for Summer Camp? - June 13, 2022