At Tarkington Elementary on the Southwest Side, kids are talking science and doing science. Sadly, that’s news. As a mom, I can say my own 4th-grade daughter hasn’t done enough real science in her elementary school years. And study after study shows she’s not alone.

What’s different at Tarkington? Teachers, supported by their principal, have made science a priority. They build in time for kids to ask questions, think things through and test ideas. Earlier this week I had a chance to visit Tarkington and take a look at high-quality science for younger students up close.

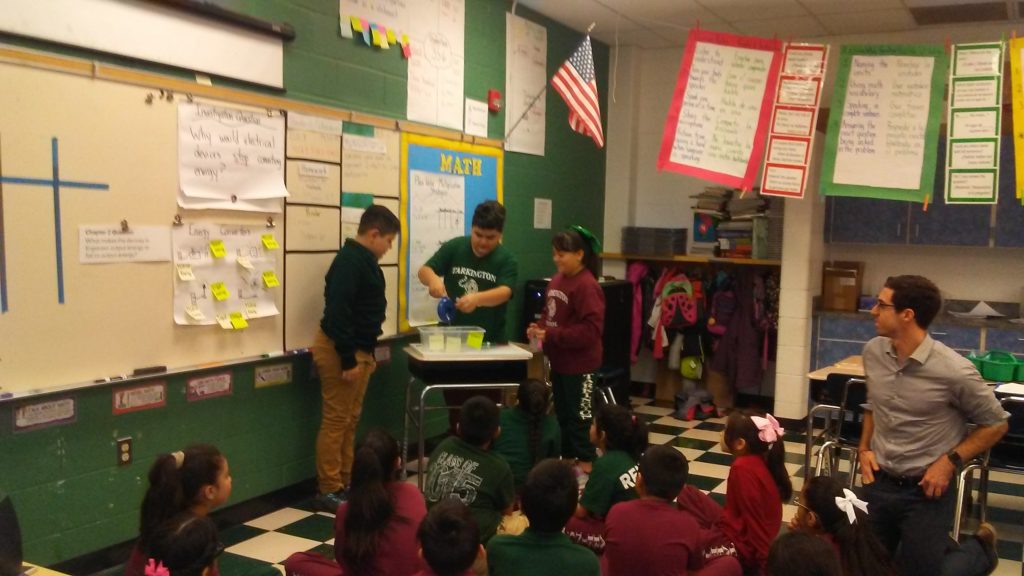

The photo at the top of the post shows a science demonstration with a fourth-grade class. Teacher Andrew DeVivo got his students thinking about electricity by considering a hypothetical situation: The power has gone out in an imaginary town, and their job is to determine how it happened and how they can prevent more outages in the future.

When I arrived, DeVivo’s class was on the rug, debating the merits of two possible power outage solutions: getting people to stop using some of their electronic devices, or replacing older streetlights with new LED streetlights. The mostly-Latinx class conversed in groups of three, speaking Spanish and English. (At Tarkington, students are encouraged to talk science in whatever language comes easiest for learning and thinking.)

Students use the cups of water and the pitcher to illustrate the finite energy available in a city’s power system and how it could be distributed using each solution. By replacing the streetlights, a large portion of the system now needs less power, shown by filling the cup to a lower level.

What really struck me in this class was the quality of science talk, from the amount of time students had to talk over ideas with each other to the way DeVivo pushed student thinking in whole-group conversation.

Hands-on, Experimental Learning

In Taissa Lau’s eighth-grade class, students are testing two kinds of toy cars that run on different batteries to see how their motion differs. In groups, they create a paper track on which to run the cars, measure distance traveled, and clock time.

In an after-class debriefing, Lau said, “They’re begging me to continue it during advisory because they didn’t get all their data.” She was also pleased at how deeply team members pushed each other to stay on top of each of their jobs in the test runs to make sure they got good data.

This year, Lau is among a number of Tarkington faculty taking a Museum of Science and Industry (MSI) course for teachers. Tarkington’s partnership with MSI runs deep. Now in its third year, the partnership connects Tarkington staff with other science-minded teachers and principals within and beyond Chicago Public Schools, reaching out to public and private schools from the suburbs and even Indiana.

Science for the Whole Family

At Tarkington’s Halloween Spooktacular Family STEM Night, families made towers using candy corn and toothpicks, then tested the towers’ ability to withstand wind.

Two years ago, Tarkington launched a three-pronged effort to infuse science more deeply into its school culture, creating Science Buddies between older and younger students, starting Family STEM Nights and creating take-home science and engineering activities for families. The three-fer strategy has now been funded by Boeing and has spread to 12 schools within the AUSL network. (Tarkington is a teaching residency school for AUSL, which manages 31 Chicago Public Schools.)

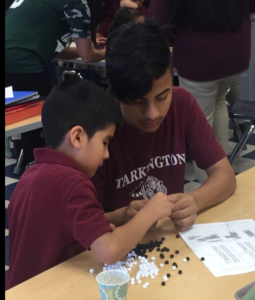

Science Buddies work together to create name bracelets using principles of binary code.

Many Chicago schools pair up seventh- and eighth-grade students with younger kids to give them an older role model. But Tarkington has been very intentional about using those buddies to promote academic learning, too. Buddies spend time doing STEM and literacy activities, which deepens academics and relationships. Buddies meet every six weeks or so. The older kids get to feel like rock stars in the hallway when their younger buddies see them, and they also sometimes get the surprise of seeing how much science their younger buddies really know. In a recent activity on motion, a kindergartner used the phrase “exert force” to describe how a ping-pong ball got moving. His older buddy said, “I just learned the word ‘exert!’ How do you know that?”

This is just a small illustration of a much larger point–when kids get exposed to science early, they learn vocabulary and habits of mind that support reading and math and contribute to the high test scores that schools are trying to pursue in less-effective ways.

At the end of my visit, science coach Kathy Bailey kindly offered me a couple of leftover take-home kits from the Halloween STEM night. Using materials like paint stirrers, cardboard and even plastic vampire fangs, the goal is to make a “candy-grabber,” a device somewhat like a DIY prosthetic arm that can pick up candy. Families got the kits in advance and took part in a contest to see whose candy-grabber could pick up the most candy and move it into a container in two minutes.

We missed the contest, but my daughter and I will be trying this out over the weekend!

Maureen Kelleher

Latest posts by Maureen Kelleher (see all)

- CPS Parents Wanted for Research Study - March 27, 2023

- Tomorrow: Cure Violence with #Belonging - August 17, 2022

- Still Looking for Summer Camp? - June 13, 2022