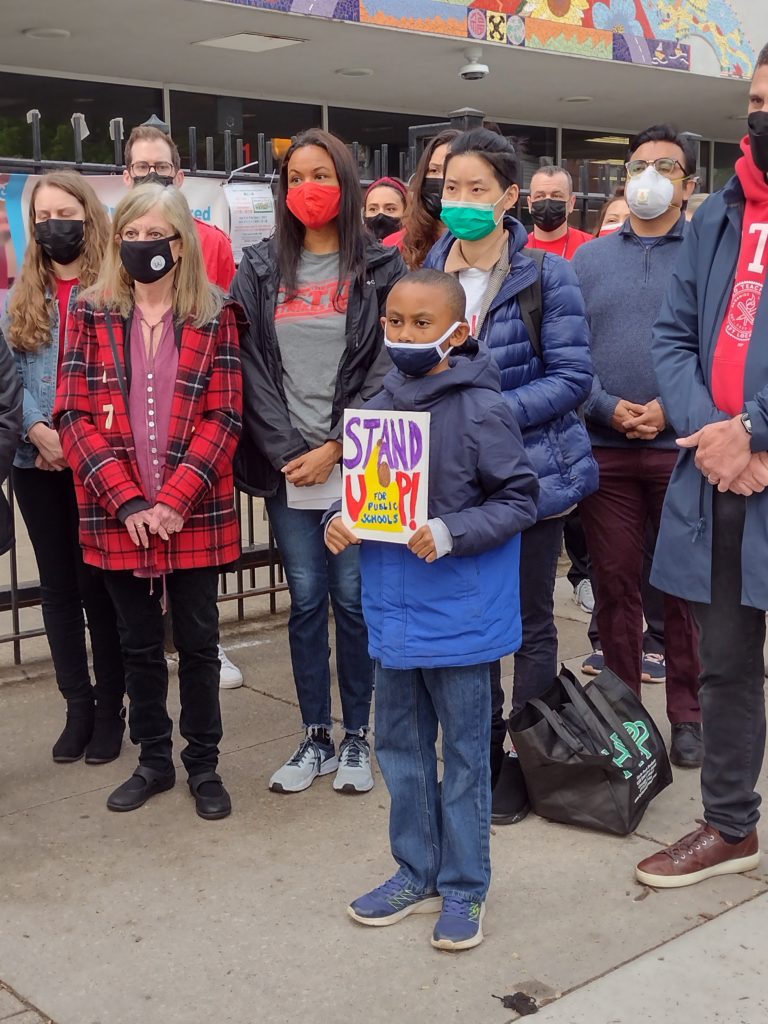

Last Thursday morning in Chinatown, Haines Elementary alum-turned-parent Wade Chan blew his stack, after taking part in a press conference protesting staffing cuts. “Why don’t we just shut down Lake Shore Drive?” he asked outgoing Chicago Teachers Union president Jesse Sharkey.

“I’m with you, bro,” Sharkey said, while also explaining the appeal process Haines can use to fight the proposed cuts.

In fact, a few hours later, the Sun-Times reported the district is restoring $24 million to schools. Chicago Public Schools officials said that money was being sent to schools as part of the yearly budgeting process, not in response to protests. Back in April, highly-visible protests at Zapata Elementary reportedly reduced their cut by about one-third, or $200,000. “We adjusted Zapata’s general education funding,” CEO Pedro Martinez confirmed in an interview, though he did not specify by how much.

All of this is taking place when the district has unspent dollars in pandemic relief funds.

What is really going on? Here’s what you need to know:

The district has two main money flows going to schools. Central office doles out one flow, for “core instruction,” based on each school’s enrollment. The principal and LSC have final say over how that money is spent. The second flow is completely controlled by the district’s central office. The funds come from many different sources, each with different strings, but all district-controlled.

During the pandemic, CPS held staffing and budgets steady at schools despite enrollment declines. Not this year. At many schools, “enrollment declines were so high, we had to make adjustments,” said CEO Pedro Martinez.

In an interview Martinez reiterated his central message: Given that the system overall is hiring 1600 new teachers, staff are simply moving from one school to another. “Every year teachers have to move from one building to another because of enrollment shifts,” he noted. “We don’t see a higher number moving this year than last year.”

Understandably, given all the disruption schools and families have faced over the last two years, parents are taking the return of the teacher shuffle extra hard. Haines parents and staff say they could lose seven positions, a mix of teachers and bilingual aides, which would make it even harder for them to serve their large population of newly-arrived Chinese-speaking students.

Increasingly, parent activists and elected officials are calling for a massive rethink on district and school budgeting. Here are a few ideas being discussed–anywhere from Twitter to yesterday’s City Council education committee hearing–that deserve a bit of explanation.

Show Us the Money

“I would like every school to be able to see how all the money that flows to that school works,“ said CPS parent and data activist Denali Dasgupta.

She envisions each school being able to see a full-color pie chart that varies in size to show year-to-year changes, and shows the sources of income as slices in the pie. Right now, schools can only see the money over which they have direct control. The CPS money won’t be visible until the Board of Education approves next year’s central district budget.

CPS also needs to better communicate its plans for federal pandemic relief funds. In an interview, Martinez asserted, “ Every ESSER dollar is being spent or being committed. We want to see a multi-year plan that is systemic.” According to Martinez, the first two rounds of ESSER money were spent doing remote learning and bringing students back into buildings.

A tension exists between using pandemic funds to fill existing budget gaps–which are considerable in many large urban centers where district enrollments have plunged–and using pandemic money in more targeted ways. In Minnesota, Minneapolis and St. Paul are taking different paths. Minneapolis has chosen to minimize disruption now by filling general budget holes, while St. Paul is taking a more targeted approach, which may include controversial school closures.

Martinez put the choice clearly: “Do we let resources stay at schools with declining enrollment? Or do we use the resources for a strong recovery plan?”

He argued that the district’s approach–recentralizing some positions, offering schools enough teachers to avoid grade-split classrooms due to overcrowding, sending schools centrally-funded (and in some cases, contractually-mandated) art teachers, counselors, nurses and a freed teacher to work closely with students needing extra help–will create more equity in the long run than continuing to hold school faculties steady when enrollment declines.

Get in Sync

Another way to ease the friction could be to better synchronize the budget and hiring cycles. Schools are bracing to lose staff because the district’s hiring and two-step budgeting processes don’t synch well.

Typically, each principal and LSC votes on its own school budget in April. This is also the prime hiring season for teachers. However, the district doesn’t approve its central budget–including the money it will send to schools with strings attached–until later.

This year, CEO Martinez is promising schools more centrally-funded positions, including art teachers, enough teachers to keep class sizes below 30 in every, and a freed teacher to work closely with students needing extra help. At the same time, he’s adjusting school-controlled budgets to keep the number of teachers in line with the number of students on the rolls.

The challenge here is that these budget shifts aren’t well-timed to keep the same staff in the same schools. If a position closes now and reopens later, the person in that slot is likely to have found another job and the school will have to open a search to someone new. That’s a loss for collegial working relationships among teachers.

It’s also a particularly huge loss for children in special education. Children with IEPs may see their teachers and classroom assistants (SECAs) for more than one year, developing strong relationships that can enhance learning.

In an interview Martinez said he wished he could keep teachers in their schools, but equity usually demands some reshuffling. “I would love for [teachers] to stay in their school, but literally they may have a school down the street that hasn’t had enough teachers all year,” he said.

Chicago Unheard asked the district directly, “What can be done to keep school faculties as stable as possible?” In response, an official statement from the Office of Communications described how the district’s talent office helps teachers and SECAs stay employed, but did not answer the question of how to keep teachers in their schools if a position closes and later reopens, based on these budgeting shifts.

According to the live-tweet thread from Raise Your hand during Friday’s City Council education committee meeting, Ald. Rosanna Rodriguez asked the district to report out all staff positions being cut or transferred from one school to another. CPS Chief Education Officer Bogdana Chkumbova said the district does not yet have such a report.

During the pandemic, the district managed to suspend those enrollment-based shifts in student-based budgeting so schools could keep their faculties stable. It’s clear Martinez is moving money and staffing back into the central budget, which could be an overall plus for equity.

But parent data advocates are digging in to understand the specifics. “I’m trying to understand their bigger game,” said Dasgupta. “They made a choice that is very significant to the enrollment narrative.”

It’s likely the public won’t see the full picture here until sometime this summer, after the Chicago Board of Education approves the central district budget.

Take a Page from the State Budget Playbook

Traditionally, school districts managed resources centrally, by assigning staff to schools and providing pots of money for specific purposes. Principals had little say over how the money coming into their schools was spent–and most of that money was tied up in staff salaries. Schools in more advantaged areas received more money, usually in the form of more experienced teachers, who earn more.

For the last eight years, Chicago has been using student-based budgeting to allocate resources to schools. Instead of receiving a set of teacher and other staff positions, plus dedicating funding for specific purposes, schools now receive a large lump sum of funds based on the number of students enrolled. Though this has given principals somewhat more flexibility and freedom to determine their staffing, schools in more advantaged areas still get more money, because declining enrollment over time has hit hardest in high-poverty, predominantly-Black schools.

How can we break out of this inequity? Some leaders are looking to Illinois’ groundbreaking work on state education funding for answers.

As newly-elected Chicago Teachers Union president Stacy Davis Gates recently told Chalkbeat Chicago, “Schools on the South and West sides are deprioritized because they don’t have students packed into every single corner. We need something that looks more like evidence-based funding at the state level.”

The evidence-based state funding formula, launched in 2018, demands the state substantially raise its investments in local districts every year and target those dollars to districts least able to raise local property taxes. Despite no new money in 2020, the new formula has made a real difference in resource equity. Many district-watchers want to see CPS adopt elements of the state system, from prioritizing the least-resourced schools for funds first to setting a standard for what constitutes sufficient resources for every school.

At the Chinatown press conference, State Rep. Theresa Mah made a similar argument. “In Springfield, we’ve worked really hard to put in place an evidence-based funding formula. … We need CPS to change the way they use our state funds at the local level. They need to do what’s right.”

Maureen Kelleher

Latest posts by Maureen Kelleher (see all)

- CPS Parents Wanted for Research Study - March 27, 2023

- Tomorrow: Cure Violence with #Belonging - August 17, 2022

- Still Looking for Summer Camp? - June 13, 2022