Principal Tawana Williams knows how people in the East Garfield Park community used to perceive Faraday Elementary School.

“They felt that Faraday was the dumping school,” she said. “They thought, for a very long time, that this was a ‘bad’ school.”

For many years, Faraday was on academic probation. The school struggled to deal with student fights and gang involvement. But over time, Williams says, she and her staff worked hard to raise the school’s performance and improve its climate — and had success.

This year, Faraday climbed to Chicago Public Schools’ highest rating, a Level 1+, after students showed some of the strongest gains in reading and math in the district. In March, CPS officials announcedthey’d chosen Faraday to become an International Baccalaureate school for primary grades as part of a $32 million initiative to improve academic programming throughout the district.

Williams knows this “elite status” will bring extra funding, world languages, field trips and partnerships to her school — and likely attract more families to Faraday.

“When you’re in an impoverished area, the belief is that even if we give [an investment] to you, it may not work,” Williams said. “But when given the opportunity, oh my god, you just watch and wait and see.”

Williams, who’s a product of CPS schools, began her career in the district as a fourth-grade teacher at Hay Elementary in the Austin community. Then she spent six years as Faraday’s assistant principal, followed by six years as its principal.

Her approach to leading the school is deeply rooted in how she learned as a child growing up in Auburn Gresham. She treasured her classroom libraries and the conversations she had with her parents around the kitchen table. That’s why she set up a kitchen table in the middle of the hallway at Faraday, complete with a red tablecloth and Vanilla Chex cereal. It’s also why she insists that each classroom has a stocked library where students can curl up with a book at their reading level.

“School is supposed to be an extension from home,” Williams told me as we toured her school in late May. “It’s not supposed to be this white sterile place where you just come for so many hours and then you leave, because then it means nothing to you.”

Williams attributes the gains at Faraday to a combination of factors. She has a core group of around eight educators who’ve worked with her for more than a decade. It’s a small school of 245 students — the district says it has capacity for 750 — that’s seen its share of budget cuts over the years, so educators have grown accustomed to doing a lot and working together as a team. Williams is fond of walking up to staff in the hallway and asking: “How many jobs do you have?”

“If it’s not personal for you, I just do not see it working,” she said.

Williams said changes also started to take root as staff began creating individual learning plans for students, and students better understood what they needed to do to improve.

“If you stop them and say ‘What’s your score? OK, what do you need help in?’ They can… [tell you] just like that,” Williams said. “We don’t have the highest scores. But each year everybody has to grow.”

This year, after analyzing student data, the Faraday staff turned a classroom into a reading intervention room for kindergarten to second-grade students. Williams said they realized many third-grade students had gaps in their reading skills, so they decided to target younger children who were struggling with phonics, sight words and letter recognition with more intensive, one-on-one supports.

Many of Faraday’s teachers also have a passion for teaching math, which has raised student interest in the subject. For example, before he went on to lead Webster Elementary, Khalid Oluewu taught math at Faraday, where Williams says he was instrumental in improving math scores for older students.

On a recent Wednesday, I watched veteran teacher Sheryl San Juaquin lead a math lesson for her split-grade class of third- and fourth-graders. Her classroom walls were covered in posters about lines and angles and how to divide fractions.

“I like the big fat Sharpies and I like to laminate everything and put smiley faces on stuff,” she told me later. “It’s part of my bubbly spirit.”

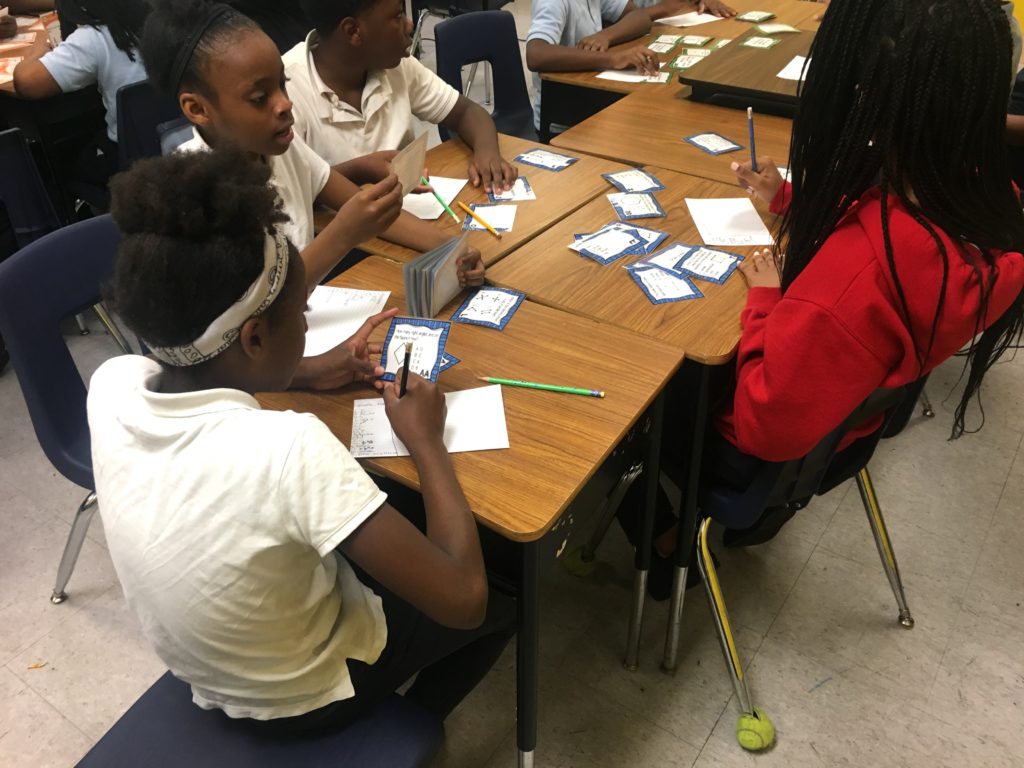

San Juaquin grouped her students by the skills they needed to work on that day and gave each table their own questions to complete. While one group reviewed lines, rays, points and angles, another worked on adding and subtracting with decimals.

Then San Juaquin staged a faceoff game where two students competed to be the first to multiply two fractions. At one point, she shifted gears, with a trivia question about an acronym for different types of figurative language, complete with a buzzer students had to press before providing their answer.

Throughout the week, San Juaquin often comes up with word scrambles or math problems to informally take stock of how her students are doing and to let them move around and let off steam. The students like the friendly competition and San Juaquin tailors the questions so it’s a fair challenge.

“I gauge who’s coming up and try to make it so they’re successful,” she said.

Even in the midst of so much success, Faraday still faces challenges. This year, every student is from a low-income family. State data show that last year, almost a third of students were homeless. Faraday consistently has one of the highest rates of students who transfer into and out of the school in the district. The school doesn’t have a full-time social worker, but many students have severe social and emotional needs.

“We’re sitting in one of the worst areas for violence in the city of Chicago,” Williams said. “We’re on lockdown at least two times a week because of things that go on in the neighborhood. But in spite of all of that, my kids still come to school and they still want to learn.”

To meet students’ needs, Faraday staff are always hunting for donations or shopping at thrift stores for supplies. Many pay out of their own pockets. The school keeps snacks on hand and readily gives out soap, toothbrushes, and laundry supplies to families. Before she bought a washer and dryer for the school, Williams used to wash students’ clothes at her house. Darlene Shorter, a school counselor who’s worked at Faraday for 12 years, says she’s seen student needs only intensify over time.

“We clothe and feed and [provide] a lot of emotional support,” Shorter said. “The need is nonstop.”

Williams said three Faraday parents were shot and killed over the last two months, a loss that’s especially difficult in a small, tight-knit school community. But after grieving that loss, there’s only one thing to do: “We keep moving,” she said. “We have to keep moving.”

Kalyn Belsha

Latest posts by Kalyn Belsha (see all)

- Sandoval Elementary Steps Up Bilingualism and Gets Results - June 17, 2019

- “We Keep Moving:” How Faraday Elementary Went from Probation to Top-Rated - June 10, 2019